Greek news outlet Kathimerini has published a new interview with Stanford University’s Bissera Pencheva who has worked with Cappella Romana as part of our Hagia Sophia project and recording. Read the interview in the original Greek at Kathimerini.gr and see the translation below:

What distinguishes Hagia Sofia from other churches and monuments of the Christian world?

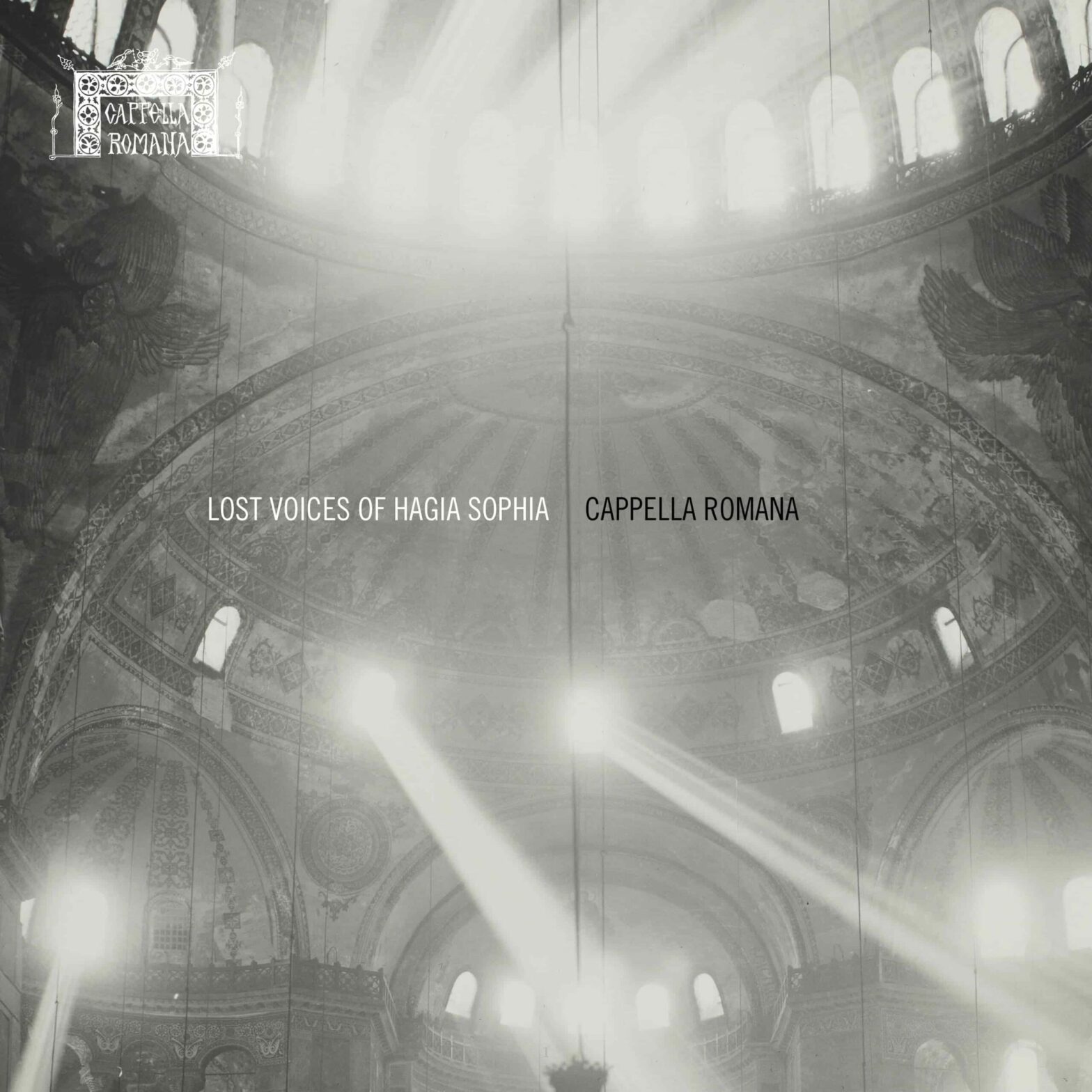

Hagia Sophia is the largest domed interior from the Middle Ages; its cupola rises over 50 meters above the floor, and no other Western medieval cathedral has achieved the same feat. The interior also preserves its authentic sixth-century marble floor, revetments, and gold mosaics. This material fabric has a chameleonic presence––poikilia––that changes appearance from gleam to incandescence by the shifts of sunrays and light moving in the space in the course of the diurnal cycle. Thus Hagia Sophia shows to this day how divine presence is manifested in the phenomenality of gold and marble, beyond anthropomorphic figuration. Sunrays penetrating the interior create paradoxical effects; the beams appear like columns of light, while the actual marble columns seem to dissolve in shadow. The book-matched Proconnesian slabs further display in their veins an uninterrupted pattern of waves that suggests the image of the lapping water of the sea. The interior with is temporal play of light mobilizes the mytho-poetic power of architecture to conjure the image of the Genesis, of the Spirit hovering over the primordial ocean. As a museum, Hagia Sophia could still be experienced as this temporal eikōn poikilē of the Holy Spirit. In winter, when the sun sets earlier in the day, the marmarygma of marble and gold becomes alive and enacts the Spirit entering matter; a body that becomes empnous. The space continues to mesmerize with its partial views, and this is what stirs the visitors to be continuously in motion, to explore by walking unhindered in the space. So even when no liturgical services are performed in this space, its form and material flux, communicate the presence of the metaphysical in the phenomenal.

As a noted international scholar on Hagia Sofia, what is your own opinion regarding Turkey’s government plans to assess whether the church becomes a mosque?

Hagia Sophia is a powerful political symbol. It anchors the modern secular identity of the Republic of Turkey as established by its founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in 1923. He encouraged the historical study of the space and already in 1931 he supported the survey of Thomas Whittemore and the Byzantine Institute of America. Based on the results of this initial study, the plan for the secularization of Hagia Sophia progressed and on November 24, 1934 the decree for the conversion of the building into a museum was announced by the Turkish Council of Ministers, the Vekiller Heyeti. The main ground for this conversion was the plan to modernize and secularize: two pillars on which the new republic’s image was built and set in contrast to the Ottoman past. The Vekiller Heyeti stated: “Owing to its historical significance, the conversion of the Hagia Sophia Mosque in Istanbul––a unique architectural monument––into a museum will gratify the entire Eastern World and will cause humanity to gain a new institution of knowledge.” What is emphasized as the reason behind this conversion into a museum is the universal, historical value of the monument and its being an “institution of knowledge.” We can hear the reverberation of this idea in the media. On March 25, 1935 an article in the newspaper “Milliyet” declared: “The conversion of Hagia Sophia to a museum, socially speaking, is a very significant event, not only in our history but also in the history of humanity. There are other examples where a shrine is assigned for another programme in history. However, all those examples––as far as we can remember–were converted after battles amongst nations. Whereas Hagia Sophia is converted from a shrine into a museum of science almost in one day in complete quietness.”

It is these concepts of universalism, respect, peace, and science that have been challenged in the recent political developments regarding the fate of the Hagia Sophia and the drive to change its jurisdiction from the control of the Ministry of Culture to that of Evkaf Umum Müdürlüğü (General Directorate of Pious Institutions).

The quotes come from Ceren Katipoğlu and Çağla Caner-Yüksel, “Hagia Sophia ‘Museum’: A Humanist Project of the Turkish Republic,” in Constructing Cultural Identity, Representing Social Power, edited by Cânâ Bilsel, Kim Esmark et al. (Pisa: Pisa University Press, 2010), 205–224.

Hagia Sofia had been a mosque for almost 5 centuries – until 1935. Did this change of religious use caused damage or affected the character of the monument?

Yes, of course there were changes, but there was also a very careful husbandry. Up until 1462 Hagia Sophia was the only Friday mosque in Istanbul. Among the immediate changes introduced in the space were the additions of mihrab, minbar, the first two minarets, and the establishment of a medrese in the grounds. The Byzantine figural mosaics were white-washed only in the second half of the seventeenth century, and this coincides with the drive to imbricate the building even further in the Ottoman sultanic ceremony and memory. This period witnesses the rise and agglomeration of royal tombs around the building: those of sultans Selim II (1566-1574), Murad III (1574-1595), Mehmed III (1595–1603). This evidence suggests that when the empire was advancing and conquering in the first century of Ottoman rule, the building was left with minimal changes. But after the end of great age of Süleyman I (1520-1566), the beginning of political stagnation led to a significant intervention in the fabric of Hagia Sophia.

This tide was reversed during the reign of Abdülmecid (1839–1862) who promoted a policy towards modernization and westernization. He invited the Swiss Fossati brothers to restore and structurally re-enforce the building. During this campaign 1847–1849, the building was first studied by Western scholars. The Fossati discovered Byzantine mosaics. When sultan Abdülmecid, saw them he was so impressed that he exclaimed: “Elles sont belles, cachez-les pourtant puisque notre religion les defend: cachez les bien, mais ne les déstruisez pas; car qui sait ce qui peut arriver?” He was right, and a new age came with Kemal Atatürk, which made the unveiling of the Byzantine fabric and study of Hagia Sophia possible.

Erdogan is challenging the legacy of the forefathers of the Turkish Republic, whose goals were respect, peace, and participation in international efforts for the preservation of the universal value of historical monuments. Erdogan rallies his Islamicist base, pushing it to the limelight and using it to eradicate the legacy of Kemal Atatürk. The Turkish people stand before a difficult choice and they have to make this decision under oppression of free speech and freedom.

If Erdogan finally turns Hagia Sofia into a mosque, would that signify a more firm distancing of Turkey from Europe and the West, a possible repositioning of Turkey as a power antagonistic to Europe? And how the Western political and academic should react to such a major decision?

I think we need to distinguish Erdogan and his Islamicist base from the rest of Turkish society. His actions go at the heart of modern, secular Turkish identity and bring pain and suffering first and foremost in the democratic spheres of that society. These are the people who challenged Erdogan and elected the democratic mayor of Istanbul: Ekrem İmamoğlu. It is their democratic voice that Europe should support and find effective ways how to do that rather than condemning Turkey as a monolith.